Make sure to follow the Broad History podcast (on Apple, Spotify, Youtube, etc...) so you never miss an episode.

When The New York Times recently asked with false naïveté, "Did Women Ruin the Workplace?" (the headline was later changed without an editor's note), I saw red like most of the Internet – but I had another reason: they hit on one of my history pet peeves.

Humanity is the richest it's ever been, and still most of us cannot afford to raise a family on a single income. Why would we think the past was any different?

Women did not suddenly spring up uninvited in the workplace in the 20th century as they burnt their bras. Far from the trad wife fantasy, women have been engaged in labor and the economy for as long as we've had an economy. I don't mean that in the "we should really incorporate the monetary value of care and house work in GDP calculations" way, though we definitely should. I mean that women have made stuff and traded stuff since at least the Stone Age. We have receipts, which I examined in conversation with economic historian Victoria Bateman in the very first episode of the Broad History podcast... which I'm happy to report is now available everywhere you listen to podcasts (Apple, Spotify, Youtube, etc...) and right here.

And if you're not into podcasts, I'm going to break down in a few paragraphs from the Great Plague to Queen Victoria how we engineered women out of the workforce and manufactured the image of the housewife. Let's go!

For most of our history, there was no such thing as a workplace distinct from the home. People lived on the land they cultivated or crafted goods in their courtyard. Even animals shared the family room at night. The economy mostly ran on small businesses to which every family member contributed. In early modern England, it was common for girls to apprentice with a master and learn a craft, as boys would. That master could well be a woman. In 15th-century London, 40% of the membership roll of the brewers' guild were women, for instance. In the records of the city's Church Courts, about three-quarters of single and widowed women and one-third of married women declared they worked for a living. (Remember, just like today, wives contributing to the family business may not have been considered or thought of themselves as employed.) Two centuries later, half the stalls at the Royal Exchange were still rented by female traders.

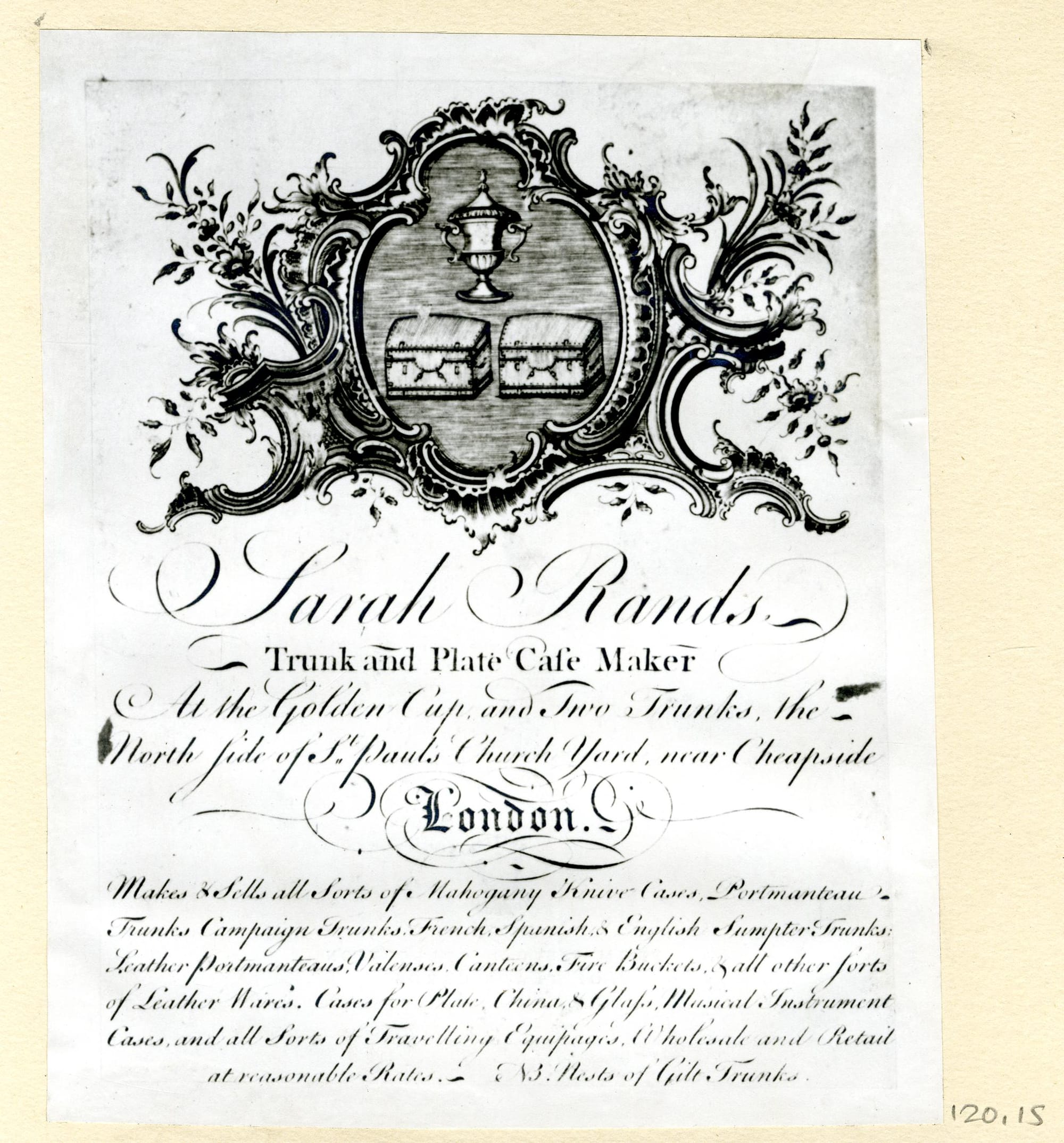

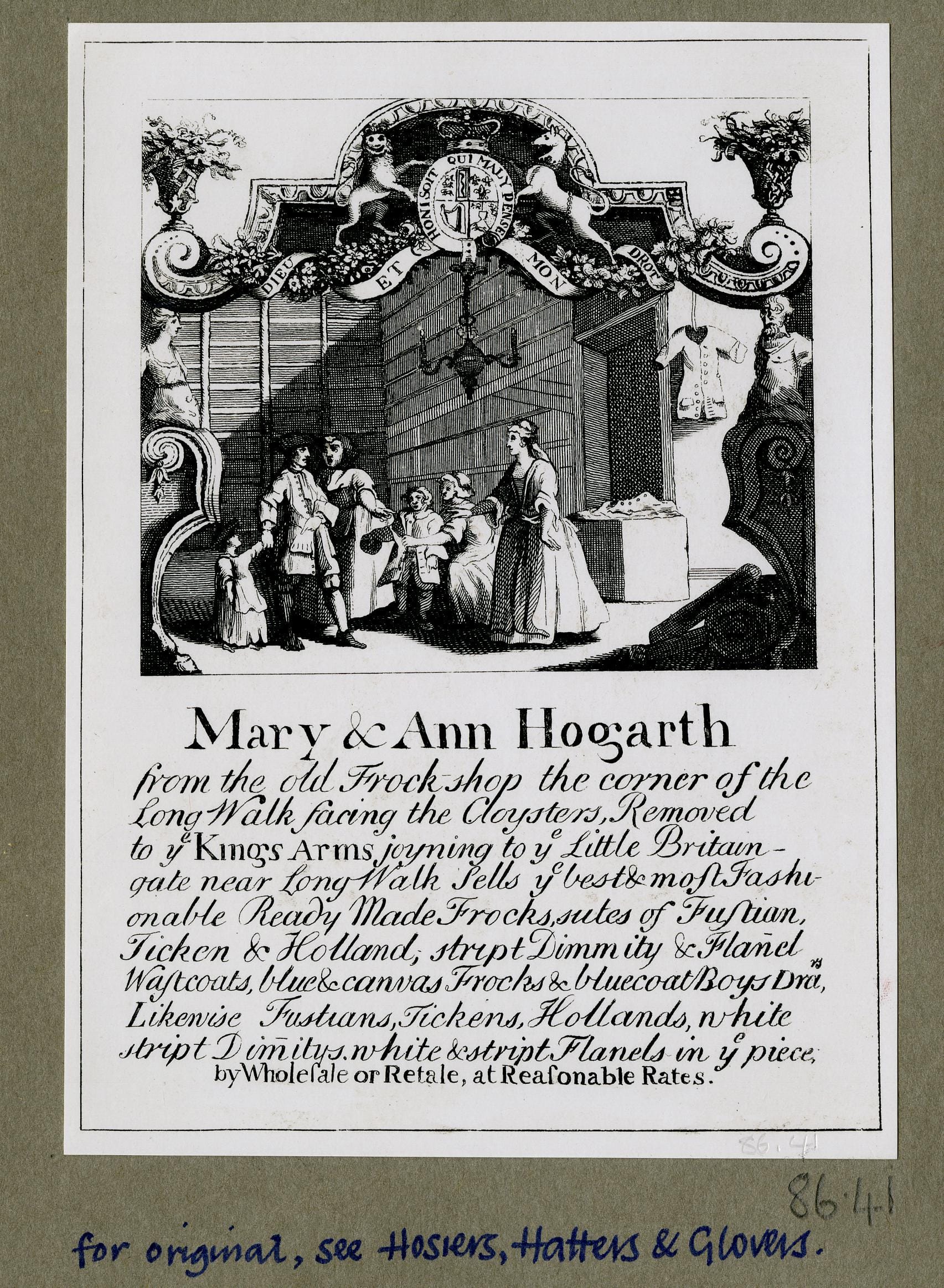

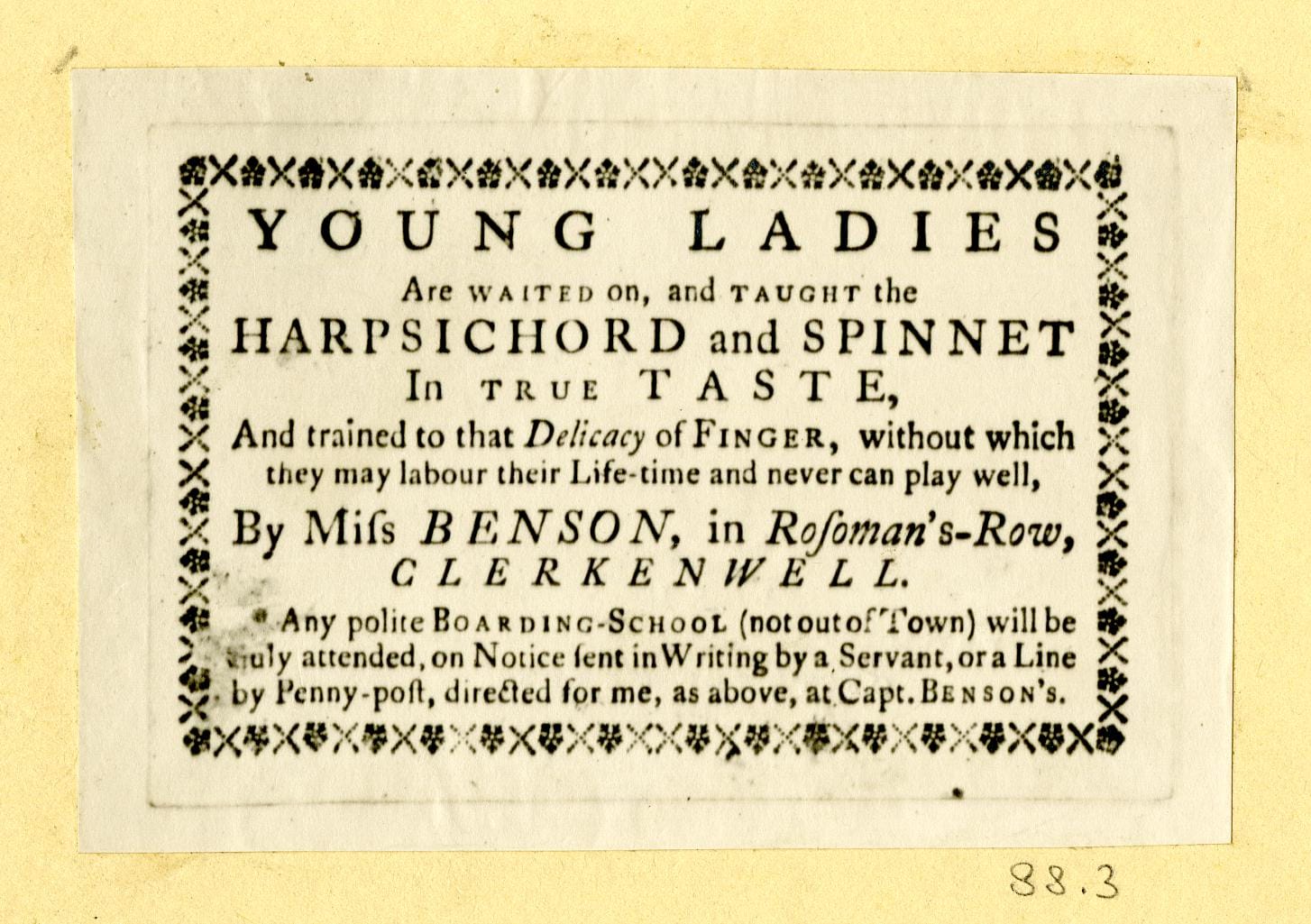

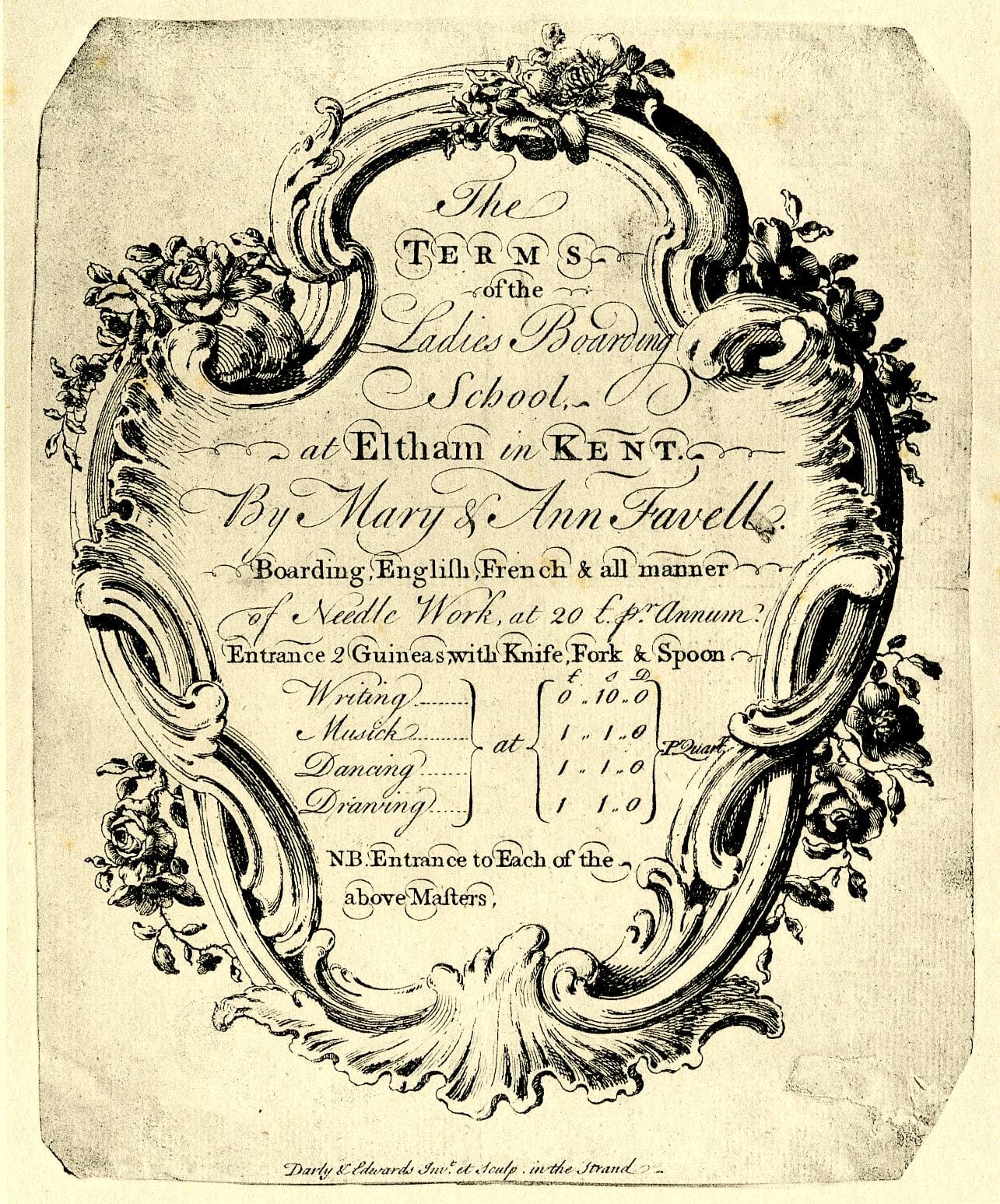

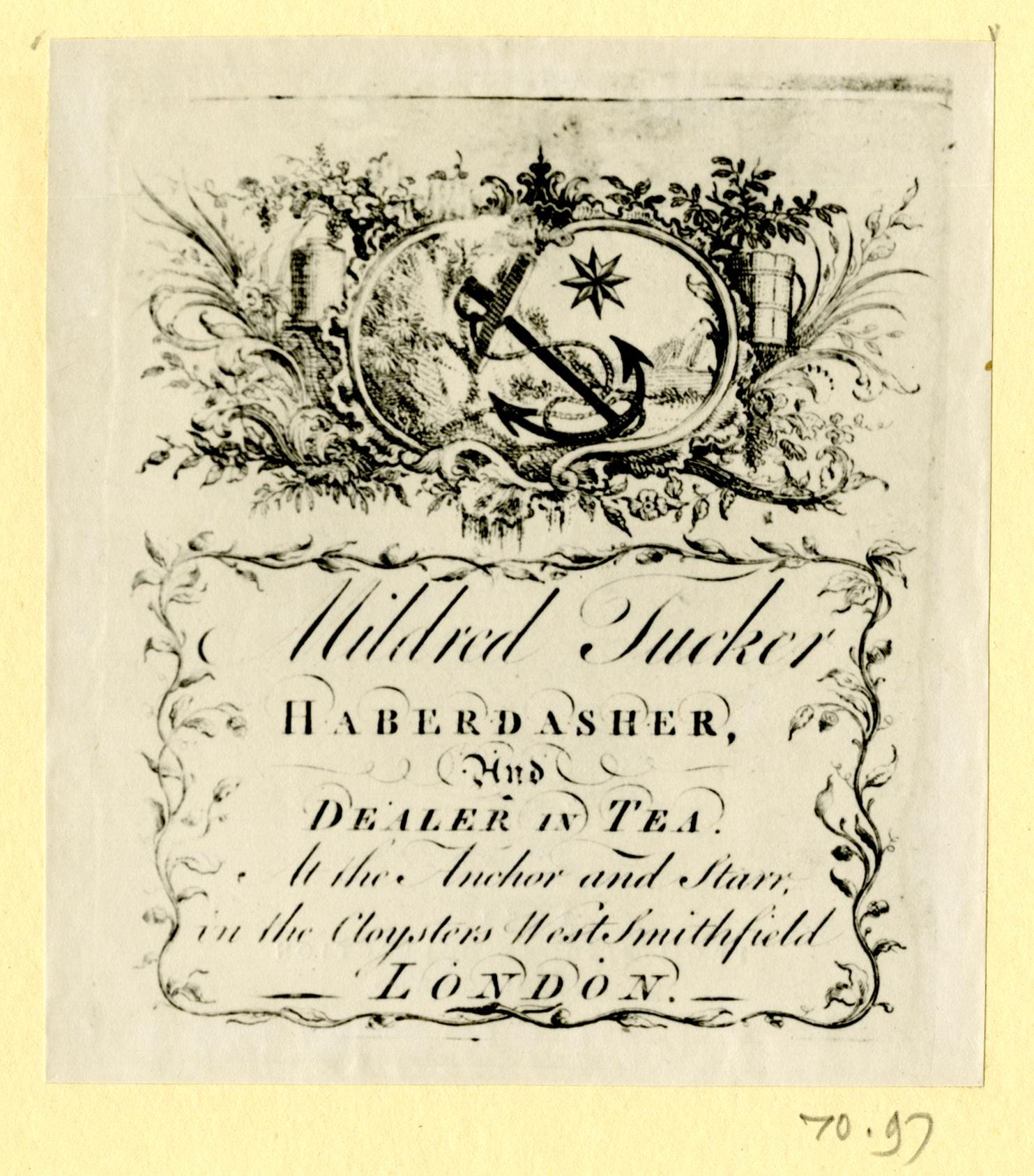

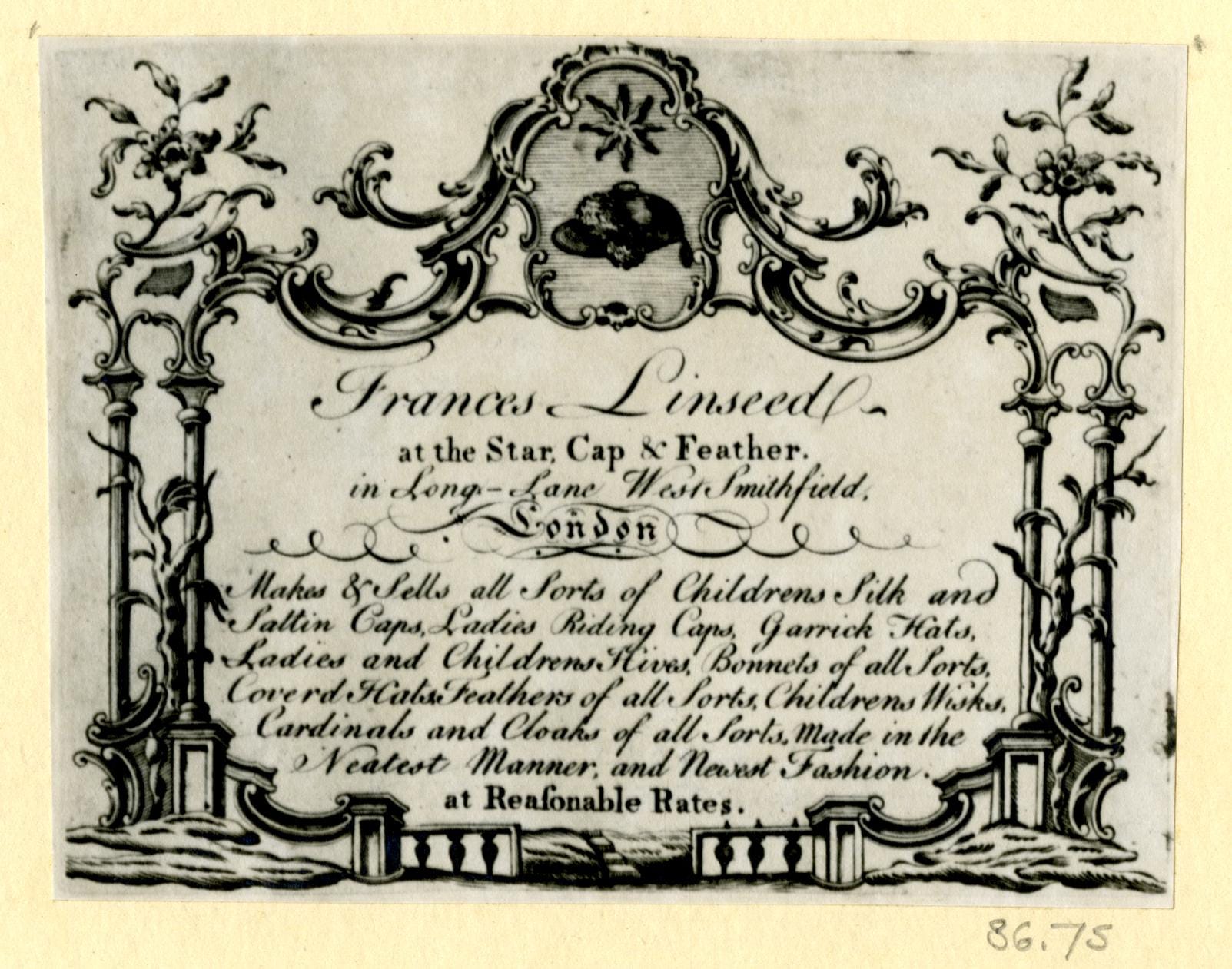

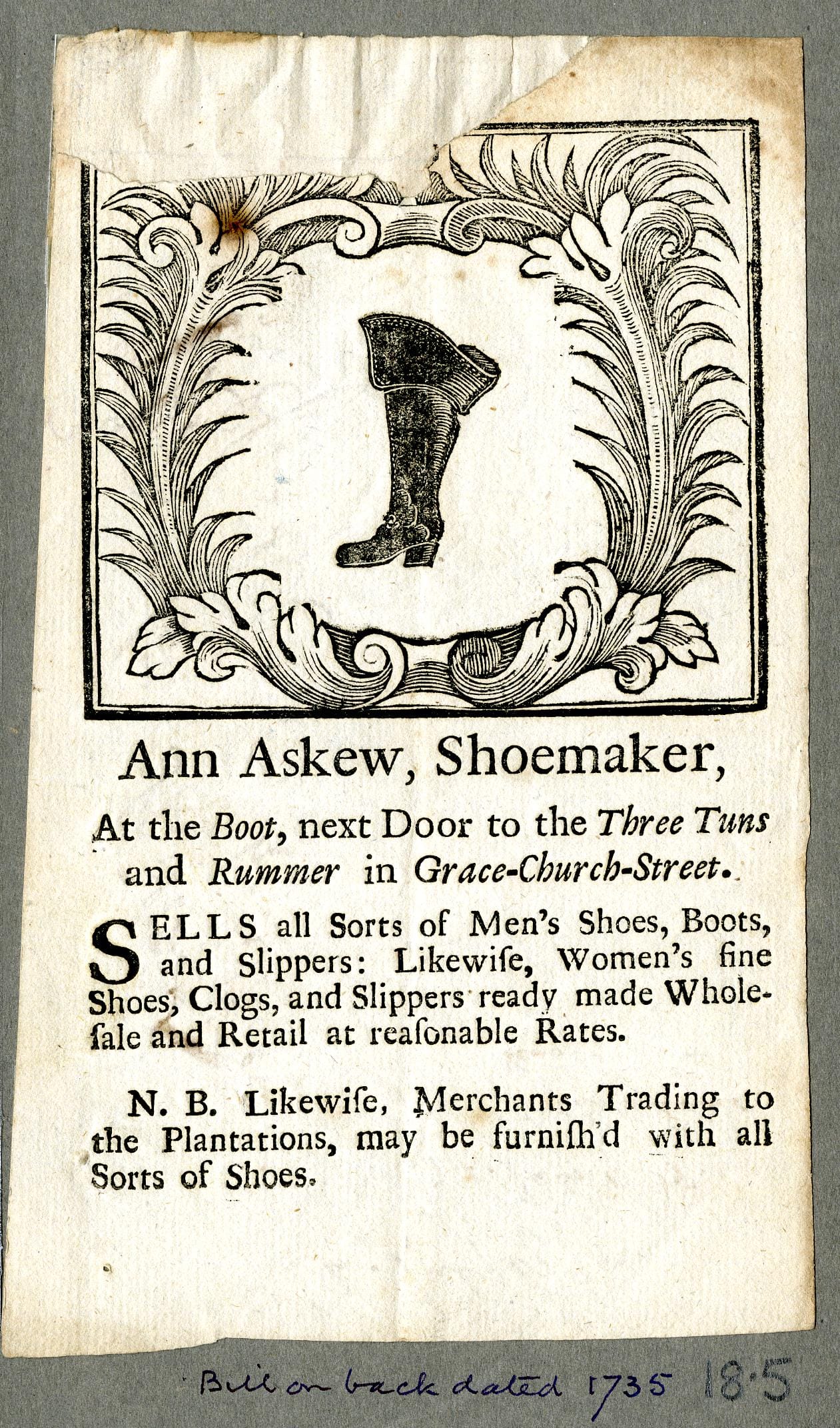

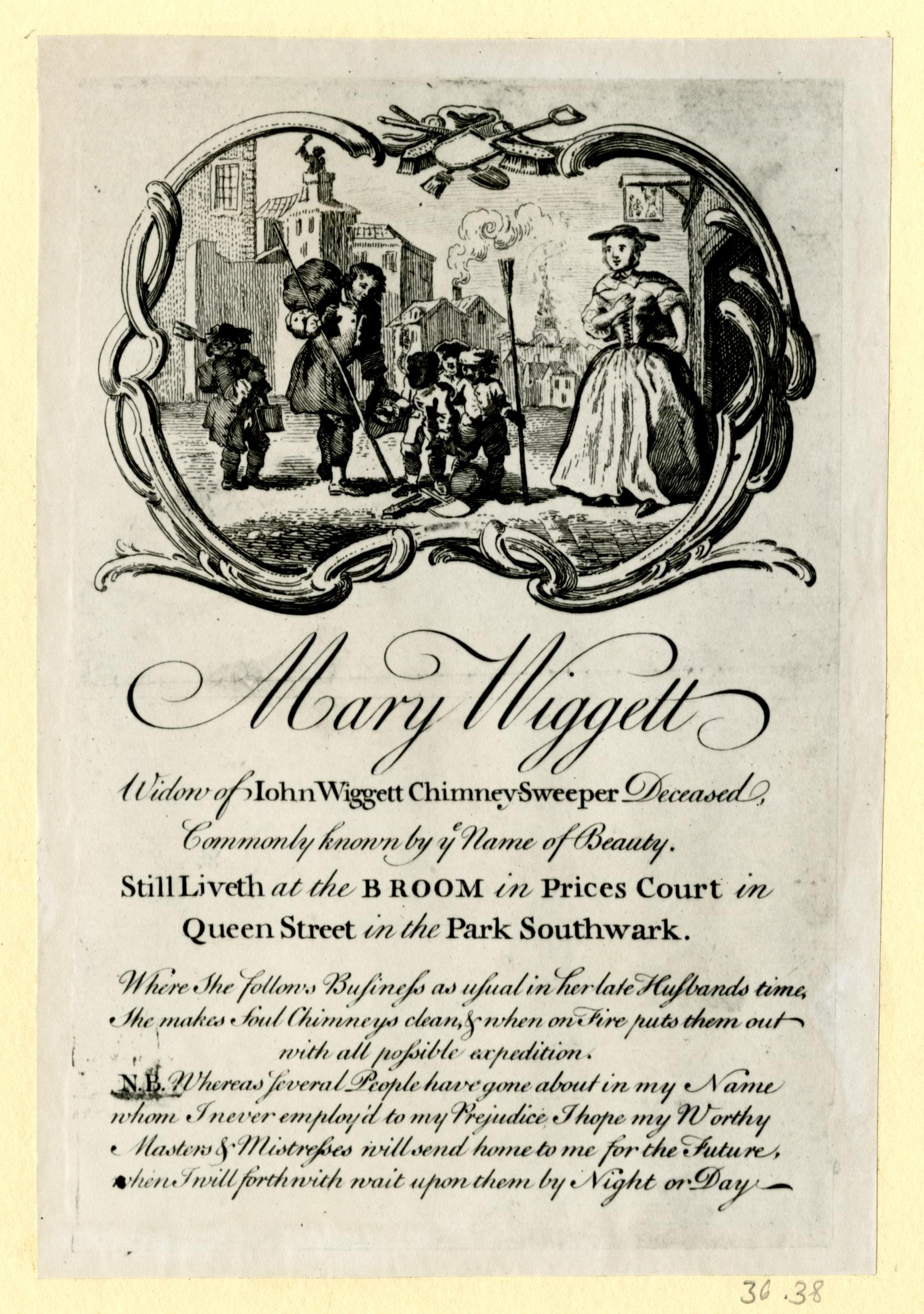

18th-century London business cards illustrate the breadth of women's economic activities. 1. Sarah Rands was a wood and leather worker making trunks and cases (c. 1760). 2. Mary and Ann Hogarth, presumably sisters, sold ready-made clothing, retail and wholesale (1807). 3. Jane Haughton ran a box-making business and was succeeded by a husband-and-wife team, John and Elizabeth Kingston (c. 1800). 4. Miss Benson advertised herself as a traveling music teacher (c. 1775). 5. Mary and Ann Favell ran a girls' boarding school in Kent (1754-1757). 6. Mildred Tucker was a haberdasher and a tea dealer (1770). 7. Catherine and John Middleton shared a business in both their names as bodice makers (c. 1735). 8. Frances Linseed was a milliner (c. 1770). 9. Ann Askew was a shoemaker (1735). All images © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

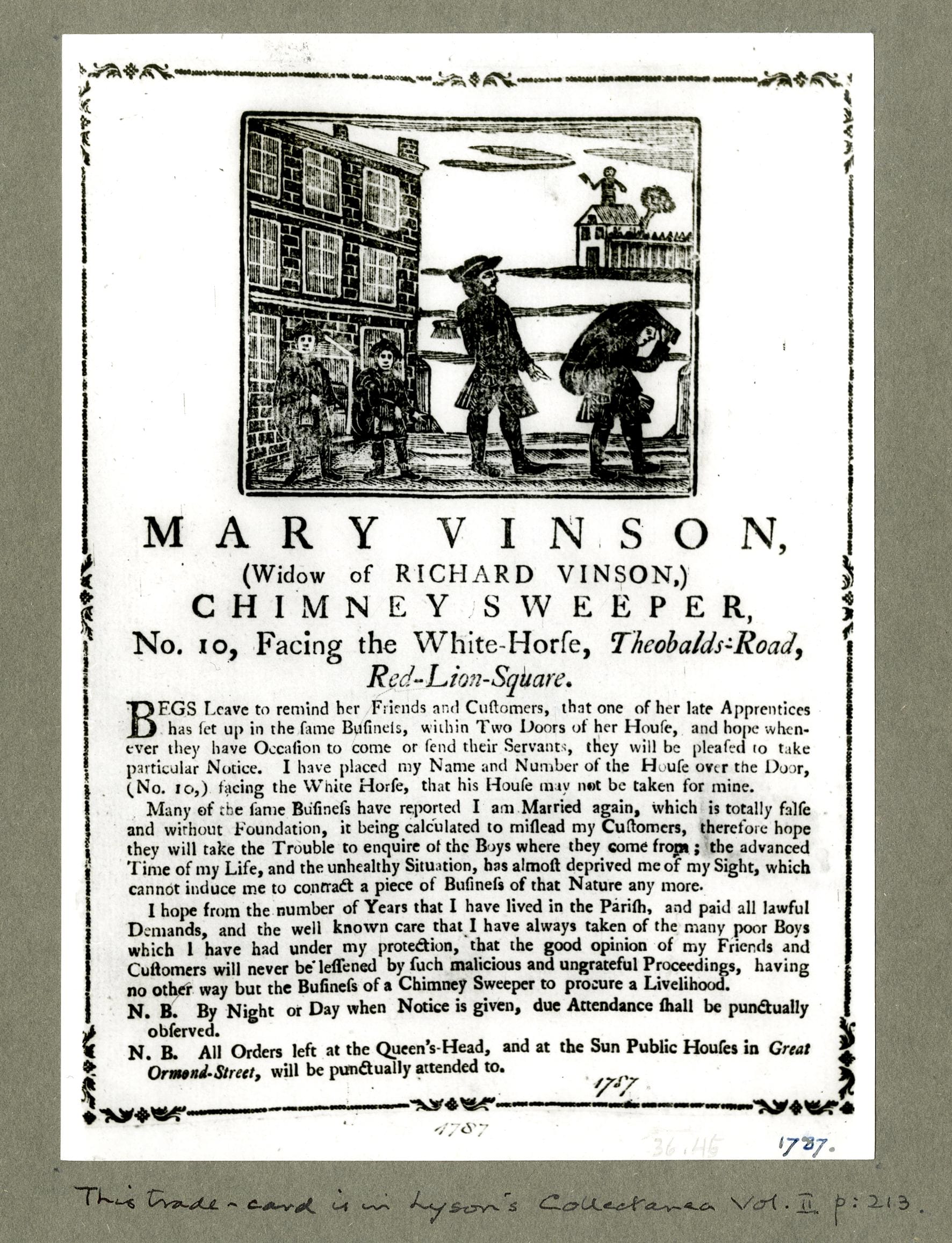

Two widows in the cut-throat business of chimney sweeping. Mary Vinson has beef: a former apprentice has set up shop two doors down and is stealing her customers. Malicious rumours are spreading that she took up with a new man. She wants the town to know she is a respectable old widow and her labor-friendly family business is her only means of subsistence (1787). Mary Wiggett is known as Beauty in this dirty business and makes sure her advertisement features her to her best advantage. She too is fighting dishonest competitors (c. 1775). © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

Though by no means an egalitarian society, the relative freedom of women in Northwestern Europe gave the region its unfair advantage and is an underestimated reason why the Industrial Revolution happened here and not somewhere else. That's one of Bateman's core arguments. To understand it, we have to go back a few centuries. I'll go quick.

Circa 1345, the Great Plague kills between a third and a half of Europe's population. You can only imagine the trauma for the survivors, but they get one good thing out of it – much more bargaining power on the job market. Suddenly, land is abundant but labor is at a premium. Elsewhere in Europe, landowners manage to impose a more authoritarian reaction and maintain serfdom. But in Britain and the Low Countries, labour comes out on top in the struggle. Wages go up and so do job opportunities for women. Able to work and earn for themselves, women gain another power – the one to refuse child marriage. At a time when almost everywhere in the world, girls marry in their teens, women in Britain marry in their mid-20s. Later marriages means smaller families. With fewer mouths to feed, parents are able to maintain a higher standard of living. This is when Brits start eating a lot of beef. They also can set money aside for their children's education and inheritance. Less population pressure on the country maintains a higher-wage economy, which encourages innovation in machines that will increase productivity. The savings invested in fewer children gives the country a better skilled workforce to make and operate those machines. It took four-ish centuries but now you have an Industrial Revolution.

The revolution they helped bring about, however, took away many of the freedoms of working women. Manufacturing moved to factories, systematically separating the home from the workplace for the first time in history. That made it harder to combine paid work with child care and marginalised labor that was still being done within the home. The spaces became gendered – the workplace masculine, the home feminine.

The exclusion of women from the workforce wasn't just an accidental consequence of geography though – it was engineered. With the advent of machines, capital regained the upper hand in the constant tug of war that is a labor market. Workers unionised in response. How could they now maintain high wages? They had to shrink the labor supply. Unions lobbied to exclude women from work. Simple math: get rid of half the competition and you'll get a better job. In order to compensate families – not women – unions pushed for the "breadwinner's wage", a higher pay for men, who were expected to provide. That guaranteed that, just like today, couples making rational decisions sent the highest earner to work and kept the lowest – the woman, by law – at home. This was packaged as a moral concern: Women who worked were said to neglect their families and were subjected to exploitative conditions. Changes in the law, sold as social progress, treated women and children as one and the same – a population deserving of special protection. The most famous such law was the Mines and Collieries Act 1842. It barred all women and girls, as well as boys under 10, from underground work in mines. The concern for their safety was real; so was the early Victorian moral panic at the sight of women wearing trousers and working bare-breasted alongside men in the bowels of the Earth. While the law did spare adult women from wildly dangerous working conditions – conditions that were just as deadly to men – it consigned them by force, not by choice, to lower paid jobs on the surface.

While working-class women were being protected whether they wanted it or not, middle-class women faced a rising qualification bar. As the economy grew more complex, it required more bookkeepers, clerks, solicitors, civil servants, doctors... The professions developed and organised in chartered societies that established entry requirements. Under the guise of maintaining professional standards, they again excluded half the competition. Guilds that for centuries had had women on their rolls started to refuse them. What had once been learned under the traditional system of apprenticeship now required some formal certification or a university degree, from which women were barred. The few professional jobs that were open to them – shopkeepers, later typists or switchboard operators – had a marriage bar. Women were let go the second they married, so that choosing a semblance of a career meant choosing celibacy – or risking one's reputation. There was little to differentiate the Victorian "New Woman", who worked or shopped in the new department stores and insisted on moving about the city, from the sex worker who walked the streets of Soho. Social enforcement was key. Home was the domain of morality.

Of course, being blocked from good work didn't change the fact most women needed to work. Married women took on home-based piece work for low-value-added manufacturing such as making brushes, mending gloves, or folding cardboard boxes. Single women were pushed into domestic service, a notoriously low-paid and exploitative situation, where they were vulnerable to sexual violence. Some were governesses, so barely educated themselves it guaranteed their charges wouldn't learn or aspire to much more. All were tucked away in homes, theirs or their employers', away from the public sphere, off the streets, out of "the workplace". Meanwhile, an increasingly consumerist society imposed new hygiene and aesthetic requirements on the Victorian home and pushed the aspiring middle classes to emulate the lifestyles of the (better off and better staffed) upper classes. There was always something to do at home. The housewife was born.

Also on this week's podcast

- The really bad science that gave us a very wrong mental image of the Stone Age

- Why cloth-making is the once and forever female industry

- Did misogyny hasten the fall of Rome?

- How the Black Death created the British pub

- What successful civilisations have in common

- and more...

Have a listen and let me know what you think or if you have follow-up questions.